This post highlights a significant paper that came out in 2023 (and the best one I read in that year) which had a major impact on applied Deep Learning (DL). Although, the center of attention was undoubtedly the release of Chat-GPT and the accompanying frenzy around Large Language Models (LLMs), this piece of research would have lasting consequences for the few years to come.

The paper is on how we can train Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) on small devices like microcontrollers. Some of you working in DL might know that the most commonly used DNNs typically take a few hundred megabytes of memory, LLMs even more, around a few gigabytes. This is when there are billions of sensors, IoT devices, etc. where DNNs could be useful but cannot be deployed because these devices are small and typically have memories in the orders of a few megabytes, so the gap to fill is a few order of magnitudes large. Some work has been done previously on inference on these small devices, like, Tensorflow Lite. But there wasn’t much talk about training DNNs on these devices. And why so?

Obviously inference itself is too difficult and when you talk of training, backward propagation, the most popular way to train DNNs is a mammoth on memory, the backward graphs, the storing of intermediate gradients, etc. can take at least as much and in most cases much more memory than the forward pass. In fact, training on these small devices would about double the memory load, compounded by the fact that in the first place you squeezed in a model for inference, so there is even lesser memory left for backward propagation. So, the budget is very tight making the problem very complex. And this is precisely the problem this paper solved.

On-Device Training Under 256KB Memory 1, by Han lab from MIT made this significant breakthrough. I have been following Assoc. Prof. Song Han for a while now, ever since his groundbreaking PhD thesis 2 in Tiny ML/Edge AI and would highly recommend reading this paper. As it is not just important but also a classic example of how complex engineering problems are solved– where you have a few innovative ideas which bundled together give you a rich solution and you can’t help admiring the creativity that went into it.

This paper combines three such ideas which are briefly described below.

1. Scaling of gradients

For compression of DNNs quantization is widely used. As an oversimplified example, consider weights of a DNN which are usually of the 32 bit float format which as the name suggests takes 32 bits. Quantization would mean representing the same weights with lesser bits, let’s take 8 bits for our example. Now casting this 32 bit number to a 8 bit number (which can be fixed point or floating) takes scaling. One way to do it is to take the maximum of all weights in a feedforward layer or a convolutional layer and divide all the weights by it. The resulting weights would be between 0 and 1 and you can cast them to 8 bit format by multiplying with 127 (the 8 bit integer range is from -128 to 127). The authors had a very clever observation with this scaling, that it distorts the gradients.

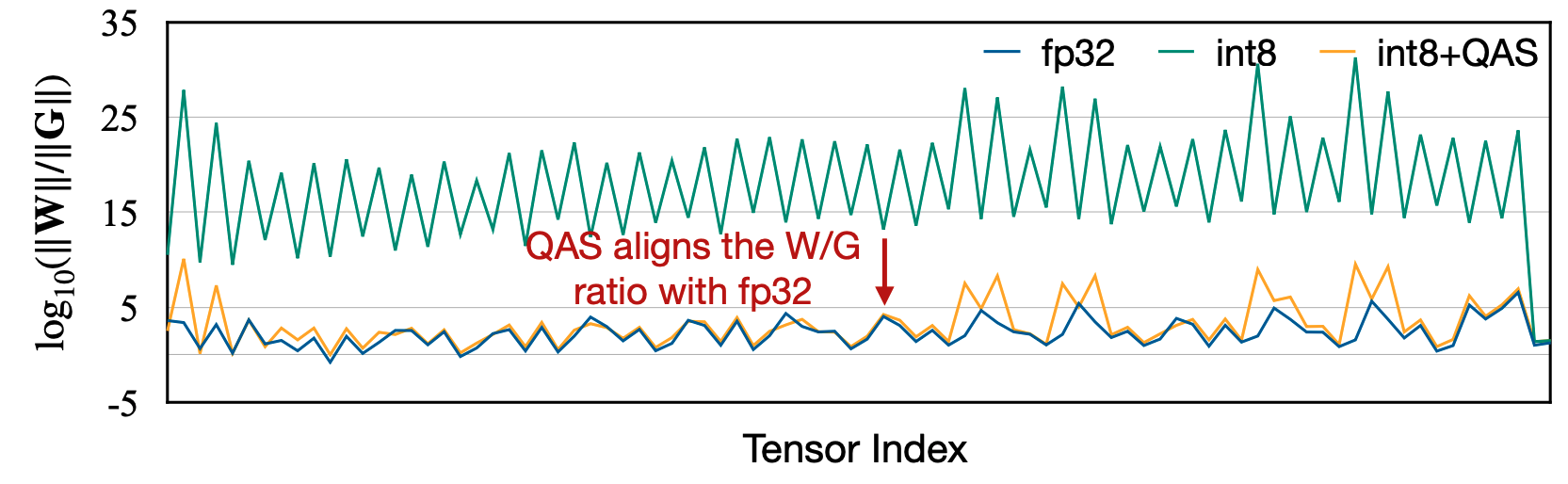

Concentrate on the green and blue lines in the graph above. The blue line represents the ratio of the norm of weights and gradients while training a DNN in 32 bits and the green line represents the same for the quantized version of training. And one can see clearly how the ratios for the latter are much higher meaning that the gradients are much smaller as compared to weights for a quantized graph. This mismatch between the two lines shows how quantizing can distort the gradient-weight ratio and hence the training process, barring training convergence to a higher accuracy.

And the solution proposed is, Quantization Aware Scaling (QAS) where they reduce this ratio mismatch by compensating the gradient by the square of the scaling factor. The QAS is shown by the yellow line in the graph and it closely matches the blue line for the unquantized 32 bits DNN.

One needs to think why the gradient of the quantized network has to be ‘compensated by the square of the scaling factor’. There is a way to understand that intuitively.

Consider the graph below of the sigmoid function \(f(x)= \frac{1}{1+e^{-x}}\). If we scale x by a factor of k, i.e. \(f(kx) = \frac{1}{1+e^{-kx}}\) the function distorts as shown in the figure. Usually, this is what one mathematically does when one wants to scale the function on the x-axis.

At the same time the gradient (or more popularly derivative) of the function is also distorted as shown in the figure below. But the derivative of \(f(x)\) distorts a little differently as compared to function \(f(dx)\).

Let’s understand this mathematically. \[ \frac{df(x)}{dx} \rightarrow derivative\ of\ original\ function \] \[ \frac{df(kx)}{d(x)} \rightarrow derivative\ of\ scaled\ function \] When weights are updated during backpropagation, we use the formula below, taking x as the weight and f(x) as the output of the layer:

\[x' = \eta \frac{df(x)}{dx} + x\] where, \(x' \rightarrow\) updated weight, \(\eta \rightarrow\) learning rate, \(x \rightarrow\) old weight, and \(\frac{df(x)}{dx} \rightarrow\) derivative w.r.t output.

For a quantized version this formula should look like: \[x' = \eta \frac{df(kx)}{dx} + kx\]

But in reality when we backpropagate we calculate the derivative w.r.t kx instead of x and in practice the equation becomes \[ x' = \eta \frac{df(kx)}{d(kx)} + kx \] Applying chain rule: \[ \frac{df(kx)}{dx} = \frac{df(kx)}{d(kx)} \frac{d(kx)}{dx} \] Where, \(\frac{d(kx)}{dx} = k\) and substituting it back to the equation \[ \frac{df(kx)}{dx} = k \frac{df(kx)}{d(kx)} \] Making the weight update rule- \[x' = \eta \frac{1}{k} \frac{df(kx)}{dx} + kx\]

This extra factor of \(\frac{1}{k}\) is what we need to compensate. Authors also argue that as x is scaled by k so the gradient needs to have an extra factor of k. Hence, we multiply the gradient by \(k^2\) compensating it and thus preserving the ratios during training.

I’ll rather quickly go over the other two tricks that the paper proposes. After all, need to encourage you to read it.

2. Sparse updates

On edge devices, we might not need to update the whole network; rather we can update only some layers whose weights and biases impact accuracy the most. They propose doing a contribution analysis of weights and biases of each layer and choosing to update only a selected few. More trends like bias update being cheap are also discussed in the paper. Sparse updates allow the backward graph of a DNN to be pruned thereby decreasing the memory footprint for training the DNN.

3. Embedded mastery

Lastly, some clever tricks in embedded programming are used in what the authors of the paper introduce as Tiny Training Engine (TTE). It creates a backward graph at compile time rather than runtime as pytorch or tensorflow. Dead code elimination, reordering operations so some can be fused together or used immediately instead of keeping them in memory, etc. are the cherry on the cake.

All this come harmoniously together enabling training DNNs on microcontrollers. Hope this brief overview kindled your interest in this line of research and if yes, do read their paper.